|

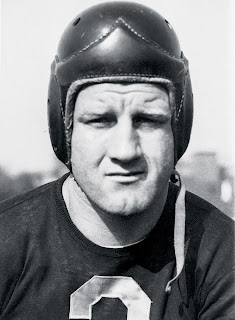

| BRONKO NAGURSKI |

Bronko went on to perform spectacularly at Minnesota, and he joined the Bears in 1930. He weighed about 235 pounds at a time when very few players exceeded 210. A fullback on offense and a tackle on defense, he was easily the best player in the NFL at both positions. He was the heart and soul of the Bears’ powerhouse teams of the early thirties.

“Bronko Nagurski was probably the greatest player I ever went up against,” said the Green Bay Packers’ Hall of Famer Clarke Hinkle. I thought to myself, ‘You either better start moving and go after him or just get the hell out of the way, because otherwise you are going to get killed.’”

In the final game of the 1932 regular season, Nagurski’s 56-yard touchdown gallop led the Bears to a 9-0 victory over the Packers amid swirling snows at Wrigley Field. The win moved the Bears into a tie with the Portsmouth Spartans for first place in the NFL, and league president Joe Carr decided to have a playoff game to settle the issue. Because Portsmouth’s stadium seated only 8,000, the first postseason game in pro football history was scheduled for Chicago.

That the NFL was still in its infancy was demonstrated by the fact that Portsmouth’s star tailback Dutch Clark, the league’s leading scorer, was not available for the game. His contract as basketball coach at Colorado College called for him to report immediately after the Spartans’ season was concluded, and it had no provision for an extra week.

The weather worsened in the days leading up to the game, with snow continuing intermittently and the temperature plummeting to below zero. Bears coach and owner George Halas recognized that few hardy souls were likely to pay hard-earned Depression dollars to sit out in a blizzard at Wrigley Field, so he got approval from the league to play the game indoors at Chicago Stadium. Inside the Stadium, a field was set up that was 20 yards shorter and 15 feet narrower than the standard.

A circus had come through the week before, and a six-inch layer of dirt remained on the Stadium’s cement floor. With rolls of sod laid on top of the dirt, the playing surface was passable and certainly safer than the frozen ground at Wrigley Field. One observer reported, however, that the arena “was a little too aromatic, what with the horses and elephants that had traipsed around there a few days before the game.”

More than 11,000 people showed up, vindicating the decision to play the game indoors. “They were exposed to the violence of professional football,” Richard Whittingham wrote, “in a way that spectators in outdoor stadiums never were. In the enclosed stadium, the sounds of impact when players blocked or tackled each other resounded through the acoustically controlled hall.”

Both defenses held sway for the first three quarters. There was only one punt returned all day, as most of them flew well into the seats. The Bears’ Red Grange was knocked out cold when he was thrown out of bounds and into the hockey boards after an end run of 15 yards. He was carted off, but soon returned. In the fourth quarter, Dick Nesbitt of the Bears intercepted a pass at the Spartans’ seven-yard line. Nagurski bulled his way down to the two on first down, but then he was stopped for virtually no gain on his next two attempts.

On fourth down and goal, the Portsmouth defenders massed in the middle of the line, convinced that Nagurski would carry the ball again. Bronko did take the handoff from quarterback Carl Brumbaugh, but instead of charging ahead, he backpedaled and lofted a pass over the scrum at the goal line. Grange was alone in the end zone to gather it in for a touchdown. Portsmouth coach Potsy Clark was apoplectic, arguing that Bronko had been too close to the line of scrimmage when he delivered the ball (at the time, one had to be at least five yards behind the line in order to throw a legal forward pass). Potsy may have been right, but the call stood.

When Clark finally calmed down and returned to the sidelines, Tiny Engebretsen kicked the extra point for the Bears. Several minutes later, a Spartan fumble rolled out of the end zone for a safety. The score of 9-0 held up, and the Bears were world champions.

The postseason playoff game stirred up so much interest that NFL owners quickly agreed to make it an annual event. Accordingly, the league was split into two divisions whose winners would meet after the season for the championship. This model remained in place until the inaugural Super Bowl after the 1966 season.

Adapted from Heydays: Great Stories in Chicago Sports

(c) 2009, 2010 by Christopher Tabbert

No comments:

Post a Comment