In 1971, two of the all-time great Chicago athletes called it a career within three weeks of each other. Ernie Banks played the last of his 2,528 games for the Cubs on September 26, and Gale Sayers played the last of his 68 games for the Bears on October 17.

| |

| GALE SAYERS |

Sadly, both players finished up as mere shadows of their former selves. Banks, 40, had only 83 at-bats for the season, hitting .193 with three

homers and six runs batted in. Sayers, just 28, played in two games and

rushed for 38 yards on 13 carries before conceding that his latest

comeback from a succession of knee surgeries had run its course. Neither man would have to wait long for the call to join his sport's hall of fame.

|

| TONY ESPOSITO |

The Blackhawks took an immediate liking to their new home in the NHL's Western Division, where they were the only established franchise among six four-year-old expansion teams. The Hawks won 26 and tied 5 of their first 37 games. They did not lose on home ice until January 6, compiling a home record of 16-0-2 prior to that. They ended up at 49-20-9, racking up 107 points to win the division going away. Mainstays of the club were goalie Tony Esposito, center Stan Mikita, forwards Bobby Hull and Dennis Hull, and defensemen Bill White and Pat "Whitey" Stapleton.

In the playoffs, the Hawks dispatched the Philadelphia Flyers (four games to none) and the New York Rangers (four games to three) to advance to the Stanley Cup Final against the Montreal Canadiens. The Hawks won the first two games at home, dropped the next two at Montreal, then won again at home--in a 2-0 shutout by Esposito--to draw tantalizingly close to capturing the Cup. But the Canadiens won the next game in Montreal to even the series again.

In Game 7 at the Stadium on May 18, Dennis Hull tallied in the last minute of the first period on a power play and Danny O'Shea lit the lamp seven minutes into the second to give the Hawks a 2-0 lead. The home team was closing in on the championship, and the old barn was rocking. Alas, the Canadiens scored three unanswered goals--two in the second period and one in the third--to win 3-2. As Montreal captain Jean Beliveau hoisted the Cup, the standing-room-only crowd of heartbroken Hawks fans politely applauded the champions. The trophy that Beliveau held in his hands would remain beyond the Hawks' grasp for 39 more years.

|

| CHET WALKER |

In their fifth year of existence, the Bulls had their first

50-win season in 1970-71. They played an intense, physical style of ball

that mirrored the pugnacious personality of their coach, Dick Motta,

and they had the Stadium turnstiles spinning. Forwards Bob Love and Chet Walker were All-Stars, guard Jerry Sloan was named second-team

All-Defense, and Motta was voted Coach of the Year. Although the Bulls

lost a hard-fought first-round playoff series to the Los Angeles Lakers

in seven games, with the home team winning each game, the future was

still bright. They won 50 or more games in each of the next three

seasons, and they proved that a pro basketball franchise could not only

survive but thrive in Chicago.

|

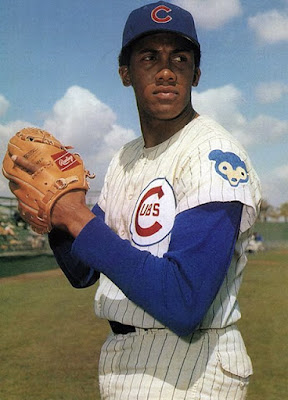

| FERGIE JENKINS |

The Cubs plodded to an 83-79 mark in Banks's 19th and final season, finishing tied for third place in the National League East, 14 games behind the Pittsburgh Pirates. The lanky 28-year-old righthander Fergie Jenkins went 24-13 with a 2.77 earned-run average and 277 strikeouts to earn the Cy Young Award. It was the fifth of six consecutive seasons in which Jenkins won 20 or more games. Jenkins was joined at the All-Star Game by second baseman Glenn Beckert, shortstop Don Kessinger, and third baseman Ron Santo. (Jenkins and Santo were among 19 future Hall of Famers who played in the ’71 midsummer classic, the most star-studded baseball game of all time.)

A late-season clubhouse meeting almost turned into a free-for-all when manager Leo Durocher made some comments about Santo that caused the latter to attack him. After Santo was restrained and order restored, first baseman Joe Pepitone and pitcher Milt Pappas also got earfuls from Durocher, who then threatened to quit but was talked out of it by general manager John Holland.

|

| WILBUR WOOD |

Having bottomed out with a 56-106 record the year before, the White Sox

welcomed a new manager, Chuck Tanner, a new broadcaster, Harry

Caray, and a return to respectability. The Sox finished at

79-83, and attendance at Comiskey Park nearly doubled. Tanner and

pitching coach Johnny Sain converted knuckleballing lefty reliever

Wilbur Wood into a starter, and the experiment proved a success, to say

the least. Wood went 22-13 with a 1.91 ERA while logging 334 innings. He

finished third in Cy Young balloting and established himself as the

South Siders' ace for the next several years. Wood and 25-year-old third

baseman Bill Melton, who led the American League (and tied his own club

record) with 33 home runs, represented the Sox in the All-Star Game.

|

| DICK BUTKUS |

After several years of mediocrity, the Bears galvanized fans by winning six of their first nine games. On November 14 against the Washington Redskins, a 40-yard touchdown run by Cyril Pinder tied the score 15-15 late in the fourth quarter. On the extra-point attempt, the snap went awry, but holder Bobby Douglass (also the Bears' quarterback) picked up the ball, scrambled around a while, and then fired a strike to Dick Butkus (of all people) in the corner of the end zone to give the Bears a dramatic 16-15 win.

At 6-3, the Bears seemed headed for the playoffs, but they lost the next five games--four of them by very lopsided scores--to finish 6-8. Head coach Jim Dooley was fired after compiling a record of 20-36 for four seasons. He was replaced by Abe Gibron.

The Bears' game at Detroit on October 24 was marred by the on-field death of Lions receiver Chuck Hughes from an apparent heart attack.

Check out our book Heydays: Great Stories in Chicago Sports on Amazon.