|

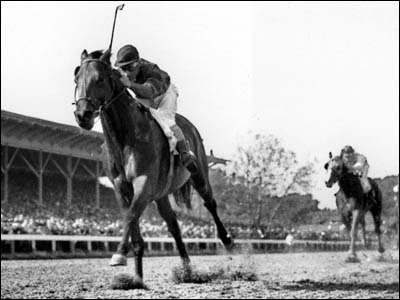

| CITATION WITH EDDIE ARCARO UP |

The difficulty of getting to the Derby, let alone winning it, is illustrated by the unfortunate case of Eskendereya. He was the runaway winner of the Fountain of Youth Stakes and the Wood Memorial earlier this spring and would have been a heavy favorite in the Derby but for an injury sustained last week in training. Eskendereya's injury appears to be relatively minor, but even if he comes back and wins many more races, he will never add his name to the list of Kentucky Derby winners.

That prestigious roll will add its 136th name tomorrow. The previous 135 include eleven that have gone on to win the Preakness and Belmont Stakes, thus completing the Triple Crown. Will this year's Derby winner join that extremely select club? Probably not. No horse has since 1978, when Affirmed followed Seattle Slew (1977) and Secretariat (1973) to make it three Triple Crown winners in six years. Prior to that, there was a Triple Crown drought stretching back to Citation in 1948.And now we've gotten to the point, which is to recall Citation, one of the very greatest race horses of all time (most experts rank Man O' War above him, and some rank Secretariat above him, but few rank any others above him). A recap of Citation's career in Chicago can be found below.

Citation first came to Chicago in the summer of 1947, his two-year-old season. On July 24, he captured the Sealeggy Purse at Arlington Park, covering the five furlongs in 58 seconds flat for a new track record. He won his first stakes race, the Elementary, six days later at Washington Park. On August 16, he and two stablemates entered the Washington Park Futurity. They were trained by the famous father-and-son team of Ben and Jimmy Jones, who won the Kentucky Derby eight times between them.

“We ran three horses in the Futurity that year,” Jimmy Jones later recalled, “and we figured we’d take the first three places with Citation, Bewitch, and Free America. So we told the riders before the race that we would split the fees three ways. That way nobody would do anything foolish in the drive. Bewitch, with Doug Dodson up, got the lead and finished a length in front of Citation, with Free America third. Steve Brooks, on Citation, said he could have gone by [Bewitch] at any time.” It was the only defeat of the year for Citation, who went eight-for-nine and was voted champion two-year-old colt. Bewitch was champion two-year-old filly.

In 1948, Citation enjoyed the greatest three-year-old campaign of all time. He won 19 of 20 starts and earned $709,470 (the previous record for earnings in a single year was $424,195). He not only swept the Triple Crown races with astonishing ease, but he also won the Jersey Derby between the Preakness and the Belmont! “Citation is by far the greatest horse I’ve ever ridden,” said jockey Eddie Arcaro, and even curmudgeonly old-timers began to mention him in the same breath as the legendary Man O’ War, who had died at the age of 30 the year before.

Fresh from his Triple Crown triumph, Citation returned to Arlington Park for the Stars & Stripes Handicap against older horses on July 5. That no three-year-old had won, and only one had run in the money, in the 20-year history of the event was of no concern to Citation. Before a huge crowd of 46,490, he romped to a two-length victory and tied the track record for a mile and an eighth at 1:49.2.

Citation got a well-deserved six-week vacation, then devastated his rivals in an allowance sprint at Washington Park on August 21. A week later, the entry of Citation and Free America was sent off at odds of 1-10 in the American Derby, also at Washington Park. The race went true to form, as Citation scored by a length over Free America in a brisk 2:01.6 for the mile and a quarter. It was his ninth consecutive win. By the end of the year, the streak had reached 15, and Citation’s career mark stood at 27 wins and two seconds in 29 starts.

An ankle injury sidelined Citation for all of 1949, but, because his owners were intent on making him the first equine millionaire, he came back to race 16 more times in 1950 and 1951. He lost on several occasions, in the words of racing writer Joe Hirsch, to “horses who couldn’t warm him up when he was right.” Nonetheless, he went out in style, winning his last three races to bring his lifetime earnings to $1,085,760.

Citation made his final public appearance on July 29, 1951. While thousands cheered, he galloped down the home stretch at Arlington Park, then was led to that place he knew so well—the winner’s circle.

Adapted from Heydays: Great Stories in Chicago Sports

(c)2009, 2010 by Christopher Tabbert