The Cubs and White Sox took divergent paths to the first

single-city World Series in 1906. The Cubs blasted out of the gate and

never looked back, racking up a phenomenal record of 116-36—still the

best of all time—and outdistancing the defending world-champion New York

Giants by 20 games. The White Sox started slowly, crept over .500 in

mid-June, won 19 straight in August to assume first place, fell back

into second several times in September, and finally surged to the finish

line three games ahead of the New York Yankees (then known as the

Highlanders).

|

| 1906 WORLD SERIES AT WEST SIDE GROUNDS. |

The Cubs led the National League in hitting, fielding, and

pitching. They scored 80 more runs than the second-best offensive team

and yielded 89 fewer than the second-best defensive team. They got

better as the season went on, winning 50 of their last 57 games. They

were 56-21 at home and 60-15 on the road. When asked whether he was

amazed that the Cubs had won 116 games, pitcher Ed Reulbach said, “I

wonder how we came to lose 36.”

First baseman and manager Frank Chance led the league in stolen bases with 57 and runs scored with 102;

third baseman Harry Steinfeldt tied for the lead in runs batted in with

83. Between them on the infield were Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers, the

shortstop and second baseman later immortalized with Chance in the most

famous baseball poem after “Casey at the Bat.” Johnny Kling was one of

the finest catchers of his day, the first in the majors to throw from a

crouch. Pitchers Mordecai “Three-Finger” Brown, Jack Pfiester, and

Reulbach finished one-two-three in the league in earned-run average;

Brown’s figure of 1.04 remains the best ever by a National Leaguer.

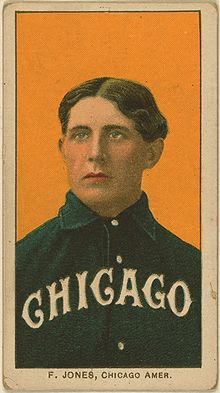

Against this juggernaut stood a White Sox club disparagingly

nicknamed “the Hitless Wonders.” Their anemic .230 team batting average

and puny total of seven home runs both ranked last in the American

League. “It must be admitted,” Fred Lieb wrote, “that [manager] Fielder Jones won his pennant with mirrors.” Lieb should have said mirrors and

pitching, for the Sox posted 32 shutouts. Frank Owen, Nick Altrock, and

Doc White won 22, 20, and 18 games, respectively, and White’s ERA of

1.52 led the league. Ed Walsh added 17 victories, 10 of them shutouts.

The cocky 25-year-old Walsh, described as “the only man who could strut

while standing still,” had just mastered the spitball (which was then

legal) after two years of trial and error. He was destined for the Hall

of Fame.

To an extent that has probably not been equaled since, Chicagoans

in the first decade of the 20th century were absolutely mad about

baseball. “All the honors worth winning,” an anonymous Tribune writer

gushed, “in the most sensational, record-breaking, and most financially

successful season in baseball’s history belong to Chicago, admittedly

the greatest, most loyal, and enthusiastic baseball city in the world.”

Chicago’s huge population of recent immigrants from Germany and

Ireland was neatly divided in its loyalties. The Germans favored the

Cubs, whose roster included Solly Hofman, Kling, Pfiester, Reulbach,

Steinfeldt, Jimmy Sheckard, and Frank “Wildfire” Schulte. The Irish

supported the White Sox, who featured Jiggs Donahue, Patsy Dougherty, Ed McFarland, John O’Neill, Billy Sullivan, Walsh, and White.

Although the Sox’ record of 93-58 was excellent, it nonetheless

would have placed them 17½ games off the pace set by the Cubs. It was no

surprise, then, that the South Siders were overwhelming underdogs to

their West Side rivals (the Cubs didn’t move to the North Side until

1916). But Giants manager John McGraw, for one, wasn’t so sure. “They

say the White Sox won the flag without hitting,” he said, “but I know

better. Their grounds prevent anyone from hitting heavily, and as they

played 77 games there, it made their averages look very small. On the

road, they hit as hard as anybody.” It was true that the Sox’ very

spacious home field, South Side Park at 39th and Princeton, contributed

substantially to the apparent futility of their hitters and mastery of

their pitchers. (When owner Charles Comiskey built his new park in 1910,

he gave it, at Walsh’s urging, similarly gargantuan dimensions.)

The Cubs were being called the mightiest ballclub ever to take the

field. They had good reason to be confident as they opened the Series

with their ace, Mordecai Brown, on the mound. He’d had 26 victories in

this first of his six consecutive years with 20 or more. Walsh was

slated to oppose Brown in what would have been a dream matchup, but

(according to legend) Sox manager Jones changed his mind at the last

minute because he believed that Walsh’s spitballs would freeze in the

unseasonably cold air. So the two future Hall of Famers

did not face each other. Altrock went to the hill for the Sox.

Game 1 was played in the Cubs’ park, the West Side Grounds at Polk

and Lincoln (now Wolcott), on October 9. “Never was such a contest, for

such high stakes, played under worse conditions,” the Tribune reported.

“A cold, raw day was made more disagreeable by a chilling wind, and cold

gray clouds denied the sun more than a single, fleeting chance to light

up the picture.” Snowflakes floated over the crowd of 12,693.

Brown and Altrock were sharp, and the game was scoreless for four

innings. In the fifth, Sox third baseman George Rohe drove one past Cubs

left fielder Sheckard for a triple. Rohe, a seldom-used benchwarmer who

was playing only because George Davis was injured, would figure

prominently throughout the Series. He scored the Sox’ first run when

Dougherty tapped a weak bouncer back to Brown, whose throw home somehow

eluded the usually sure-handed Kling.

Brown committed the cardinal sin of walking Altrock, a .152 hitter,

to lead off the sixth. Altrock moved to second on a sacrifice by Eddie Hahn, then tried to score on Jones’s single to center. But Hofman’s

throw to Kling was perfect, retiring Altrock while Jones took second.

Jones then advanced to third on a passed ball by Kling and scored on Frank Isbell’s single to left.

Leading off the bottom of the sixth, Kling walked. Brown twice

failed to bunt him to second, then swung away and singled over the

middle. After Hofman sacrificed, Altrock threw a wild pitch that scored

Kling and pushed Brown to third. But Brown, representing the tying run,

went no further. First, shortstop Lee Tannehill raced back into shallow

left to make an over-the-shoulder grab of a blooper by Sheckard. Then

first baseman Donahue stretched to scoop Rohe’s low throw out of the

dirt, retiring Schulte and the side.

Altrock clung to the narrow lead for three more innings, and when

it was over he and the Sox had escaped with a 2-1 win. “One swallow does

not make a summer,” Cubs owner Charles W. Murphy remarked. “And I might add

one snowstorm does not make a winter, but it keeps fans away from ball

games.”

Game 2 was played before 12,595 at South Side Park, also amid snow

flurries. The Cubs scored early and often, knocking White out after

three innings and roughing up his successor, Owen, as well. They pounded

out 10 hits and seven runs. Reulbach, meanwhile, allowed but one hit

and one unearned run. In three different innings he walked the first

batter and in another he hit the first man up, but only in one of these

instances did the man reach second base. Brilliant fielding by the Cubs

repeatedly rescued Reulbach from his self-imposed peril, and the Series

was tied up. “That’s one and one,” said Comiskey. “And we’ll be there

with the right kind of goods tomorrow.”

Walsh, the right kind of goods, started Game 3 against the Cubs’

Pfiester. The weather had improved markedly, and 13,667 showed up at the

West Side Grounds. They saw a superb pitching duel in which neither

team scored for five innings. In the top of the sixth, the Sox loaded

the bases with none out. Pfiester didn’t give in. He got Jones on a foul

pop-up to Kling, who leaned well into the crowd behind the plate to

make a fine catch. Then Pfiester fanned Isbell. He was on the verge of

squeezing out of the jam when the unknown Rohe came up. Rohe hit the

first pitch down the left-field line, where it bounced into the crowd

for a ground-rule triple. The three runs were all that Walsh needed as

he scattered two harmless hits and struck out 12. The Sox won 3-0.

Game 4, played before 18,384 at South Side Park on October 12,

featured a rematch between Brown and Altrock, who had battled memorably

in Game 1. George Davis was back in action for the Sox, replacing

Tannehill at shortstop while Rohe remained at third base. Right fielder

and leadoff man Hahn was also in the lineup, unfazed by the broken nose

sustained when he was hit by a pitch in the previous game. “They can

hand me the beanball or push my nose aside every day in the week,” he

said, “if the Sox can only win.” Hahn singled with two outs in the sixth

for the Sox’ first hit off Brown, but he was stranded. In the seventh,

he lost Chance’s drive in the sun and allowed it to fall for a single.

Two successive bunts moved Chance to third, and Evers’s solid single to

left scored him with the only run of the game.

Brown blanked the Sox on two hits. In the ninth inning, with two

out and the potential tying and winning runs on base, he was literally

knocked down by a vicious shot off the bat of Isbell. He recovered both

his bearings and the ball in time to throw to Chance for the game’s

final out.

Altrock was philosophical about finding himself on the short end of

the 1-0 score. “There is no great loss,” he said, “without its

compensating gain. Had I won this game and another, the irksome ethics

of this profession would compel me to wear a collar and necktie all

winter.”

Part 1 of 2.